So I’m sure we’ve all heard about Pavlov—the Russian physiologist—and his classically conditioned dogs. You know, the ones that started to salivate at the sound of a bell?

The story and variables behind classical conditioning are known on a widespread-surface level, but educating yourself on the depths of this topic will prove to not only be interesting, but also relatable. Eventually, the connection to taste aversions will become clear, but we’ll need to start at the beginning.

The Background

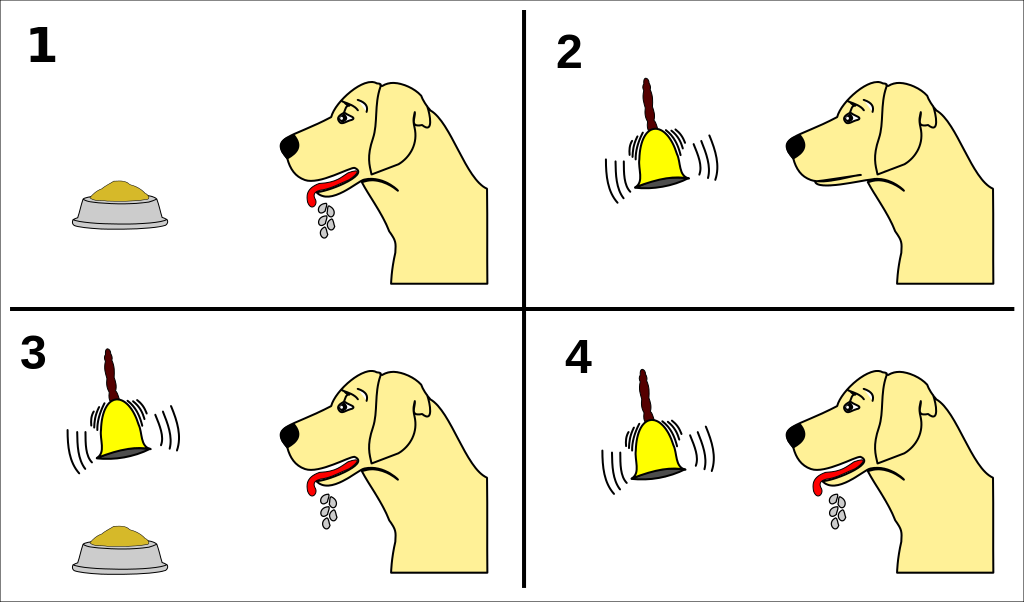

Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Okay, so what the heck was Ivan Pavlov doing in a lab with a bunch of dogs and meat powder? He was interested in digestive enzymes, so he was testing K-9 saliva—yum.

In the course of his testing, Pavlov noticed that the dogs began to salivate before the meat powder was actually delivered to their mouths. The sound of the researchers’ footsteps, for example, made those dogs start to drool.

This inspired further experimentation and resulted in a huge breakthrough in psychology and the field of learning. Pavlov was on his way to discovering how people and animals learn by associating stimuli with each other. Of course this idea of pairing stimuli doesn’t seem like a revolutionary idea now, but at the end of the 19th century, this was a huge deal.

The Basic Terms

This article is irrelevant if you don’t know the difference between an unconditioned and conditioned stimulus, so it’s time to define some terms.

Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Unconditioned stimulus (US):

The variable stimulus that has no learned association with it. In the case of Pavlov’s dogs, the US is the meat powder.

Unconditioned response (UR):

This is an automatic—and therefore not learned—behavior. The UR in this situation is the dogs salivating, because that is a natural response to being presented with food (or meat powder).

Conditioned stimulus (CS):

A stimulus that starts out neutral but grows to have an association. The bell originally had no meaning to these dogs, but after reinforced trials, they learned that this bell signaled food.

Conditioned response (CR):

The resulting behavior after the CS is presented. The CR (as well as the UR) is salivation. It’s important to note that the CR and UR can often be the same behavior, or the CR can look like behavior in anticipation of the US.

A Contemporary Example

GIF courtesy of giphy.com

Where are my The Office fans at? This one’s for you to take a moment to reminisce on Jim and Dwight’s relationship and Jim’s flawless pranking abilities.

For the true fans, I’m sure you already know exactly what I’m about to say. There was the episode where Jim classically conditioned Dwight to hold out his hand at the sound of a computer rebooting. Jim’s work productivity was compromised in his experiment, but I think we’ll all agree it was worth it.

Ok, so what’s your task? Watch this video, and try to identify the following variables: unconditioned stimulus, unconditioned response, conditioned stimulus, and conditioned response.

Think you have your answer? Were your respective responses to the above variables: “do you want an Altoid?”, holding out a hand, the computer sound, and (again) holding out a hand?

If so, give yourself a pat on the back. If not, join the club because I also got confused during this example in my Psych 1 class. It gets easier with practice, I promise.

How It Relates

GIF courtesy of giphy.com

Hopefully you have a better understanding of what classical conditioning is. To emphasize it again, a formal definition is placed for your convenience below.

Classical Conditioning:

A neutral stimulus is paired with a meaningful stimulus to produce a conditioned response.

This sounds fairly intuitive because we encounter this kind of stuff everyday. When your dog sees you grab his or her collar, they might start jumping up and down because they have paired the collar (US) with going for a walk. This kind of learning requires many reinforced trials, pairings of the CS and US, before the conditioned response will take place.

More Terms

There’s more to classical conditioning than just defining the stimuli and responses.

Acquisition:

The learning period where the CR is established. More effective learning takes place if the time between the pairing of the CS and the US is extremely short.

Reconditioning:

Beginning to use reinforced trials again after a break.

Stimulus generalization:

A range of stimuli that are similar to the CS that will elicit the same or a similar response as the CR.

Stimulus discrimination:

A distinction between the CS and other stimuli that are used in unreinforced trials.

Higher-order conditioning:

Animals develop a classically conditioned response to previously neutral stimuli that are later paired with the CS. Think about pairing the bell and meat powder with a specific toy. The dog can then be classically conditioned to salivate at the sight of the toy.

Extinction:

After many trials where the US is not paired with the CS, the response to the CS goes away.

Spontaneous Recovery:

After many unreinforced trials, pairing the US and CS elicits the CR.

Your Taste Aversion

GIF courtesy of giphy.com

What even is a taste aversion? It’s a learned response to foods that make you feel ill. Typically, food aversions can be learned after just one trial. Another key feature of taste aversions is the time between the conditioned and unconditioned stimulus is not extremely time sensitive.

Imagine you eat a big bowl of spaghetti and hours later find yourself throwing up for hours over the trash can. Whether caused by spoiled spaghetti or a stomach virus, you’re now fairly likely to get sick at the thought, sight, smell, or taste of spaghetti. It sucks. But, it’s also interesting to explore what causes this.

Let’s break it down. The spaghetti started as a neutral stimulus because it did not generate the lovely response of puking. However, the association between the spaghetti and your sickness conditioned you to view the spaghetti as the conditioned stimulus.

GIF courtesy of giphy.com

What about stimulus generalization? Maybe now every time you encounter any type of pasta you start to feel queasy. This kinda sounds like the end of the world, but it’s entirely possible because the stimuli are similar enough that your learned association of spaghetti and throwing up expands into other food areas of your life.

On the other hand, we have stimulus discrimination. This is the ability to determine a difference between conditioned stimulus and other stimuli so as to create a less pronounced or no conditioned response. For example, you can identify lo mein noodles as being different than spaghetti noodles and not respond to them with an uncomfortable feeling.

GIF courtesy of giphy.com

Now what about the other variables? We have the spaghetti as our conditioned stimulus, and the avoidance or ill-feelings associated with the spaghetti is the conditioned response. The unconditioned stimulus in this example is throwing up (either as a result of a virus or merely stuffing yourself to the point of vomiting) because your body does not have to be trained to react that way to an unpleasant situation.

The unconditioned response? An inherent avoidance of something that makes you sick. No one should have to tell you not to eat a rotting piece of food—it’s unconditioned.

In order to extinguish this horrid taste aversion and corresponding undesirable reactions, you must encounter repeated trials of the conditioned stimulus (the food) without the unconditioned stimulus (the nausea, headache, stomach pain, etc. from the virus).

This is a step-by-step process. You can start by looking at pictures of the food, move on to being in the same room as the food, start becoming comfortable to take a whiff of it, and slowly, ever so slowly, you can attempt to take your first bite.

The danger lays within the possibility of your body responding horribly yet again, and reinforcing that taste aversion. Having yet another less-than-desirable experience with this same food could strengthen your taste aversion even further. Maybe you gotta risk it for the biscuit?

GIF courtesy of giphy.com

Taste aversions are tricky because the variables are not intuitively drawn from the principles of classical conditioning. It’s also important to point out that trying out a new food and then feeling sick from it because you don’t enjoy how it tastes is not a taste aversion. In this scenario, the food did not start off as a neutral stimulus because the thought of it already made you feel a bit iffy.

And there you have it. Hopefully you’ve learned something new about classical conditioning and food learning. And the reasons why that tequila will just never be the same after last weekend.