I don’t like French food.

When I decided to attend culinary school, however, I applied to an old institution that teaches only French cuisine (which will remain unnamed, due to their strict media policies) without hesitation, as do many other chefs. Why, one might wonder, did I choose to train in a genre of cuisine for which I feel only lukewarm love at best?

It certainly has nothing to do with health. Nearly every recipe I made during culinary school was loaded with butter, cream, bacon, or all three. By all counts, the health-conscious next generation should be the best indicator of French fine dining’s impending death. But, as far as I can tell, it doesn’t.

Neither did “fun” or “enjoyment” factor into my decision. Obviously, you can’t attend culinary school without a deep love for food. Once there, however, you must hold onto this love with every ounce of your strength, because the long hours and hair-pulling meticulousness with which the teaching chefs will pull apart your work will threaten to squash any passion you once felt.

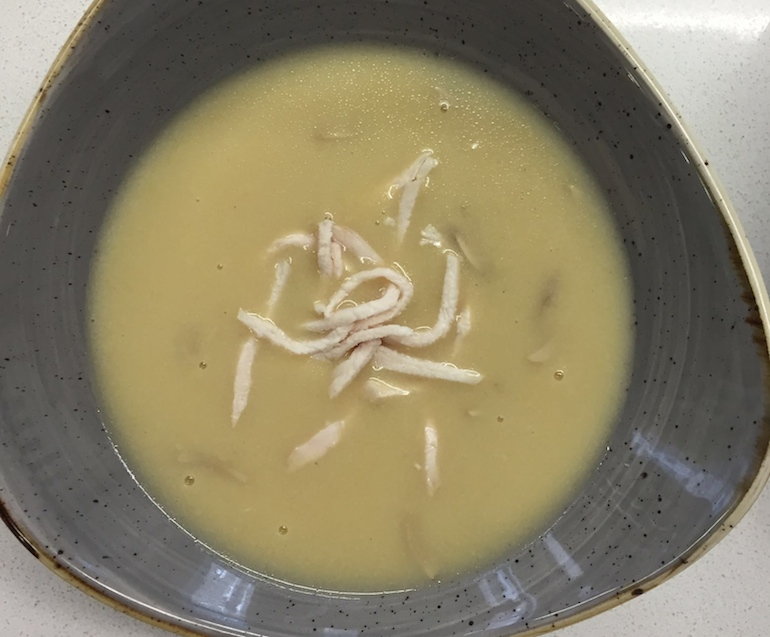

Despite all of these factors, French cuisine will never die. Even if I don’t want to eat cream and butter-rich mushroom velouté (see photo below), the skills that I acquired while learning to make that classic soup will serve me in any field of cuisine.

Photo by Emma Noyes

When I first stumbled under the gaze of a teaching chef, I cowered at his rebuff. He yelled out to the entire kitchen that I left my chef’s knife (the really big one) out at my station when I went to wash my vegetables, where anyone could have been impaled.

Later, when he told me that my julienne of carrot was slightly larger than 1 mm, my face burned with shame (see photo below for examples of different French vegetable – julienne are the thin strings on the right that were picked apart by the chef to show their inconsistency).

Photo by Emma Noyes

I left that first day wanting to quit altogether. If this was life in the kitchen, it wasn’t for me.

As the days stretched on, however, I saw the benefits of their harsh style. During cooking school, you are assigned a time at which you must plate and serve your dish to the presiding chef, which mirrors the time-restricted atmosphere of a restaurant.

Too focused on nailing my serving times, I didn’t notice that I was improving. Quickly. After all, when you only have 2 hours to clean, gut, fillet, cook, and serve an entire fish and turn it into fancy fish mousse (see photo below), you don’t realize that you just filleted an entire fish, something that used to scare the crap out of you.

Photo by Emma Noyes

By thrusting their students headfirst into the kitchen, with plenty of opportunities to fail, this style of teaching requires students to focus entirely on their work. No skimming Instagram while listening to the drone of a lecturer. Pay attention to the chef’s demonstration, or flail hopelessly at the stove.

After several weeks of arriving home at 10 pm, too tired to do anything but seek out my couch, I realized that I felt more fulfilled than any class I’d taken during my two years of college.

That’s the secret. Even though I know that, if I ever become a true chef, I won’t cook French food and I certainly won’t run my kitchen with the mind-numbing anger that characterizes so many famous chefs today, I get it now. French cuisine is inherently complex and precise, molding its students into the disciplined worker-bees that the kitchen hive requires.

From now on, when I go out to eat, I will never take a single carrot for granted, because four hours of work probably went into putting that carrot on the plate in front of me.