Trigger warning: This article includes references of eating disorder behavior.

It was September 2015 when I decided to reach out for professional help about my eating disorder. Though I came right out and admitted it on the internet, I thought I had “fixed myself” and was too embarrassed to admit to anyone that it had come back with a raging vengeance.

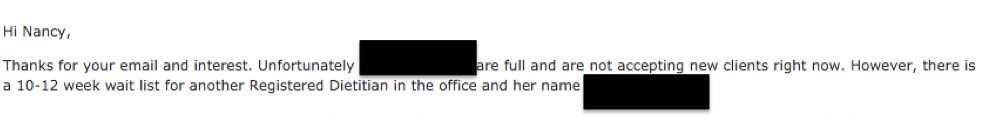

So I Googled. I contacted nutritionists, psychologists, psychiatrists. It got bad enough that I contacted intake centers, more commonly known as “rehab centers.”

Photo courtesy of Flickr user Quinn Dombrowski

I’m not a celebrity, but I wanted the peace and safety that came with going somewhere away to just focus on getting better. I remember lying on my bed, curled up in a ball of self-hatred yet still hopeful that yes, maybe I could get better; that yes, maybe one of these programs would be a miracle worker.

Unfortunately, everything was a lot harder than I thought.

Everywhere I looked, people either had waiting lists that were at least ten weeks long or they didn’t accept my insurance, or both. The intake centers I had contacted asked me questions about my eating disorder and my behavior and took my insurance information, but ultimately said that no, I wasn’t sick enough to be accepted, and no, my insurance wouldn’t cover any part of it anyway. And if I wanted any chance of ever being accepted, I needed a “team” composing of a nutritionist, a psychologist, and a physician.

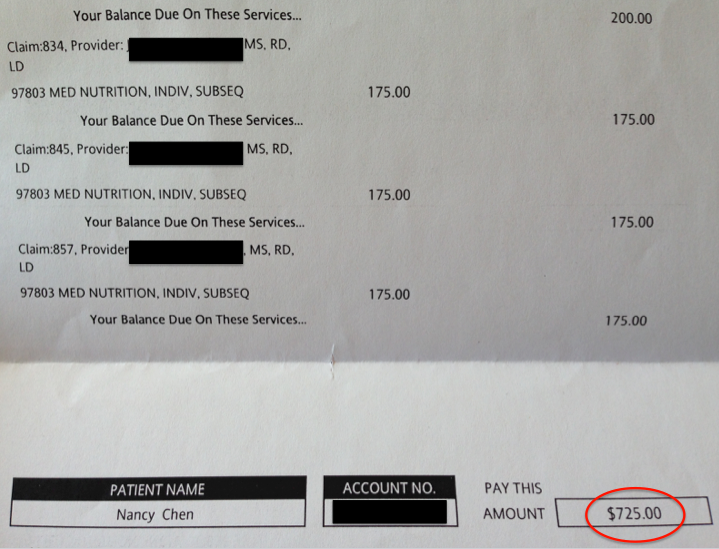

Photo by Nancy Chen

I came to the conclusion that basically you had to be rich, have a certain type of eating disorder, and be well-connected to even get medical help dealing with your eating disorder.

This is a serious problem with the American healthcare system. It’s already difficult enough for people who are struggling with eating disorders to seek help. It makes it infinitely more difficult when there are so many barriers put in their paths, like insurance refusing to cover appointments or intake centers refusing to accept patients.

Photo by Nancy Chen

When did taking steps to recover from an eating disorder become such an exclusive process?

The first issue is with the system as a whole. There are so many people with eating disorders and not enough medical resources to help them. Even for me, living in Boston, which is one of the biggest medical hubs in the country, there were not enough nutritionists, especially those that specialized in eating disorders, that I had a choice of which one to pick. It was more something along the lines of, “I hope I get to talk to even one of them.”

And with any medical specialist that deals with people with eating disorders, it’s important to find the right fit. Taking this choice away from the patient and forcing them to accept whatever specialist will see them first makes it harder for the patient to recover.

On the topic of intake centers, I believe that patients should not have to fit a certain “requirement” in order to be deemed fit to be accepted. Who is a stranger to say if you need that level of help or not? If you need help and want to be part of that program, then you should be allowed in.

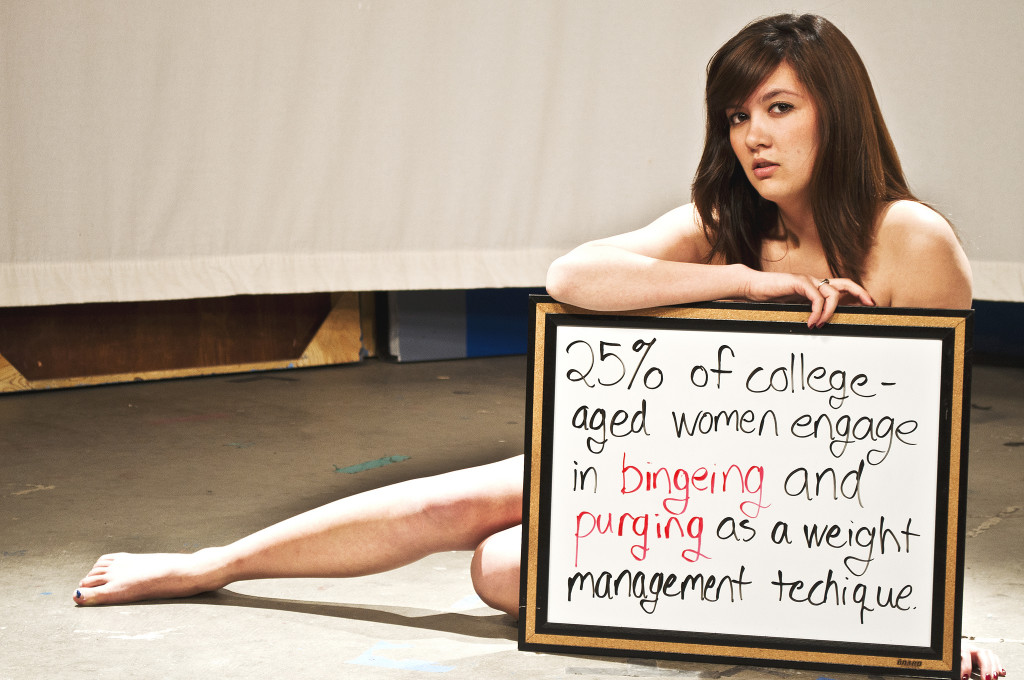

The second issue is with awareness and stereotyping. There is this stigma against speaking about eating disorders. It’s slowly disappearing, sure, but in general, eating disorders are not something you really talk about. Understandable, since it’s not a light topic, and those who have not experienced an eating disorder themselves can’t really relate.

Photo courtesy of Flickr user Mike Cicchetti

The problem with this, however, is that we turn to mass media for education on eating disorders. We look at portrayals of girls in movies and books to see what eating disorders look like. And this means that we think all anorexic girls are bone thin, that all binge eaters are obese, that all bulimics make themselves throw up all the time.

This is so, so untrue. Not only can eating disorders not be categorized into these rigid structures, but there are new eating disorders popping up. Orthorexia, which on the surface just looks like someone living an admirably healthy lifestyle. Exercise bulimia, in which you don’t actually purge by vomiting, but by overexercising after a binge.

And with the stereotypes, I can say by firsthand experience that you do not have to be underweight to be anorexic. You do not have to be obese to be a binge eater. And you do not have to necessarily throw up to be considered bulimic.

I was the picture of health, but I struggled with almost every single eating disorder.

Photo by Nancy Chen

But since I wasn’t skinny enough to be dangerously underweight, since I wasn’t overweight enough to be in risk of heart complications, since the doctors didn’t really care that I exercised to the point of passing out (because exercise is good and it keeps you healthy, right?), nobody in the healthcare system thought my problem was really serious enough to warrant much attention.

The problem continues beyond just me.

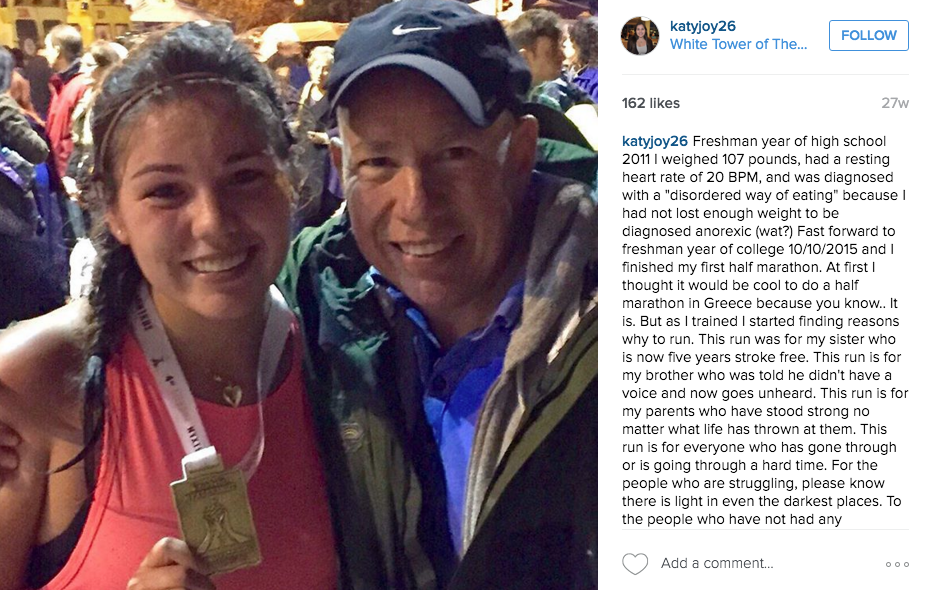

A friend was diagnosed with a “disordered way of eating” by a psychiatrist and not anorexia because she hadn’t lost enough weight.

She was 5’6 and 107 pounds. Her hair was falling out excessively; her resting heart rate was dipping into the 20’s. She was not ok, but according to the doctor, she wasn’t skinny enough to be anorexic.

Photo courtesy of @katyjoy26 on Instagram

Healthcare professionals are supposed to look beyond the stereotypes. They’re supposed to care about their patients, to nurse them back into their full mental and physical well-being.

This only shows that everyone, medical professionals or not, is subject to the stereotypes that have pervaded our society. When you tell a girl who’s not eating that she basically isn’t skinny enough, isn’t good enough, to be anorexic, then how can you think that this is helping your patient in any way?

There’s a heavy focus on anorexia in healthcare, most likely because that’s what people think when they think of eating disorders. They think, “Oh, she’s not eating. That’s dangerous, because your body needs food.”

Photo by Luna Zhang

But what about all the other forms of eating disorders that can be equally as dangerous? By ignoring them or pushing them to the side in favor of a particular type of eating disorder, we’re ignoring a huge number of people who need help.

All eating disorders are dangerous. All eating disorders should be treated equally.

It’s not ok to tell me how to eat more without addressing the fact that I had binged and how that binge was affecting my body. It’s not ok to tell me that I’m not thin or sick enough to be admitted to an intake center. It’s not ok to tell my friend that she wasn’t skinny enough to be labeled as anorexic. It’s not ok to tell someone that if you don’t look like you have an eating disorder, then you don’t have one.

I don’t have a solution to any of these issues, and I’m not saying that there aren’t amazing, helpful, life-changing nutritionists, therapists, physicians, psychologists, or psychiatrists out there. I’m just saying that from personal experience, there is a lot that needs to change in our healthcare system regarding eating disorders.

And whether that begins with education for the general public about what an eating disorder is, with having a more open conversation about eating disorders, or by insurance covering more of eating disorder treatment, so be it.