The Farm-to-Table movement is a lifestyle that is becoming increasingly popular in the United States. It concerns local food production being available to local consumers while also advocating for sustainable farming and agricultural practices.

This movement is embodied at Blue Hill at Stone Barns, the infamous farm-to-table restaurant that caught the attention of critics worldwide, and was popularized by the highly acclaimed Netflix documentary series Chef’s Table.

For my mom’s birthday, my grandma wanted to treat my family to a meal that we had all heard so much about.

Photo by Cynthia Lessick

As the waiter brought out our first course, my brother and I looked at each other and hid back our laughs. “Vegetables from the farm,” he tells us.

I look in front of me, and what I see is an array of tiny vegetables — tomatoes, fennels, baby bok choi, yellow peppers, and goose berries. Each were untouched by a stove, sauce, salt, pepper — anything to indicate to us that there was indeed a chef behind that wall.

Photo by Cathy Danh

The mission of Blue Hill is to use sustainable ingredients from local farms in order to educate on the importance of awareness of what we eat. They aim to enlighten consumers on practical and viable ways of farming and eating, something that America has seemed to lose sight of in the last century.

They place great importance on nutrition, sustainability, and efficiency to counter the mass market of processed and nutrient-poor food industries that seem to be taking over the country.

My family decided to try the unique yet pricey experience for ourselves. Courses upon courses of the freshest and most minimally prepared food came one after another, all leaving us with varying feelings, ranging from infatuation to distaste.

The plates ranged from bean stalks sprinkled with paprika, to bone marrow topped with garlic, to lamb neck prepared with homemade charcoal.

Photo by Cynthia Lessick

The experience was certainly one of a kind. However, at the end of the meal, it was time for the check.

Although there were too many courses to count, and the scenery was beautiful, and the staff worked without flaw, there was still an air of shock when looking at the bill.

We knew it was coming (they needed our credit card information before allowing us to make a reservation), but the fact that the scantily cooked and barely altered food would break down to about $350 per person felt like a rip off.

The food was good, but my family agreed that it was not the best we’ve ever had. Overall, my biggest disappointment was the price. From my perspective, most of the courses did not require much labor or cooking from a chef. It seemed like we were paying obscene amounts just to get fresh food. This is where the problem begins.

Sure, the tomatoes were unearthly fresh and the berries were insanely juicy, but why is it worth so much?

Photo by Cynthia Lessick

The entire establishment bases its structure on the principles of fresh and quality farming. This is something that I applaud greatly. The amount of time and effort that they put into growing the crispest, ripest, most nutritious, and most flavorful food they can — purely by farming — is truly inspiring and worthwhile.

But it seems like the proponents of this kind of lifestyle are ignoring one huge flaw in the system. Why is this so expensive that it is not accessible to everyone?

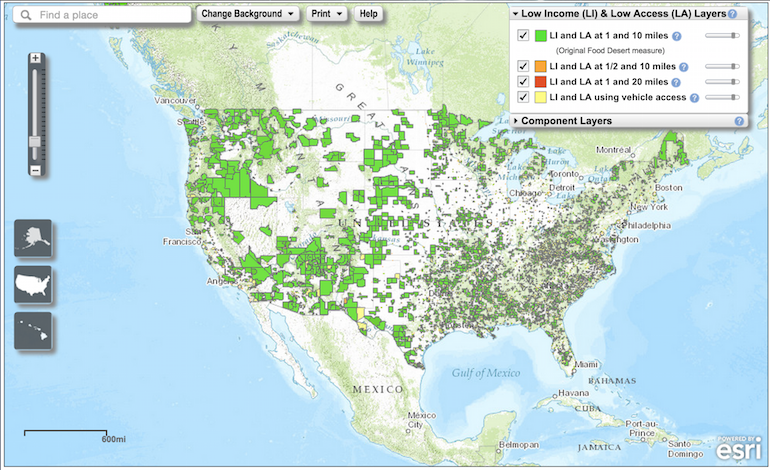

The problem is this: Currently in the United States, 23.5 million people live in food deserts.

According to the USDA, a food desert is defined as “urban neighborhoods and rural towns without ready access to fresh, healthy, and affordable food. Instead of supermarkets and grocery stores, these communities may have no food access or are served only by fast food restaurants and convenience stores that offer few healthy, affordable food options. The lack of access contributes to a poor diet and can lead to higher levels of obesity and other diet-related diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease.”

To put this into simpler terms — in our country, about 13.5% of the population cannot afford to find and eat healthy and nutritious food, and this is a large contributing factor to an epidemic of obesity, heart disease, and diabetes in the United States.

But what does this really look like? Over the summer, my friend stayed in a neighborhood of Washington DC called Petworth. She explained to me that this area of the city was considered a food desert up until a short while ago, when a Safeway supermarket was installed.

Before that, all that was available for food were little corner convenience stores and 7-Elevens with aisles of frozen, packaged, and processed foods.

It was a wake-up call to realize that when my friends and I go into 7-Elevens after a long night out searching for that box of pizza rolls, I am possibly standing in someone’s only source of food.

Photo courtesy of mummaw.com

Granted, Blue Hill is an extreme example of farm-to-table pricing. However, the contrast is simple. You can pay $350 for food that should be expected and is a necessity, such as fresh, quality ingredients. Or, you can pay for groceries with minimum wage and get processed, chemical-ridden food that poisons your body. Why are the necessities not what is available?

Farm-to-table establishments are roughly estimated to spend over 30% more on their ingredients on average, compared to restaurants that don’t put as much emphasis on sustainable farming, according to Mike Kokas, founder of Upstate Farms. This then translates to menus being more expensive, thus clientele being more wealthy.

So, before we know it, farm-to-table becomes a luxury that identifies with upper-class lifestyle, while the poorest of the poor live in areas where they cannot physically find the food they need to maintain a healthy lifestyle. When did our society become one that only allows the rich to be healthy? This system is unethical and unpractical.

Photo courtesy of usda.gov

There needs to be change. The farm-to-table movement is a worthwhile way for Americans to try to add nutrition back into our daily lives. However, we are moving in the wrong direction, and shouldn’t let trendiness deter from the bigger purpose.

In order for this action to be truly world-changing, it needs to be tailored to all types of socioeconomic groups.

We need to support small, family-owned farms who are disappearing at a frightening rate, falling from 6.8 million in 1935 to only 2.2 million in 2002, according to a recent Department of Agriculture report.

Photo courtesy of facebook.com

We need to fund these farms in areas with food deserts, so they can provide affordable and nutritious options, such as farm-to-table, for our country’s poor. It is not logical to have the basic necessity of nutrition only be attainable for the country’s most wealthy.

Blue Hill gave me the experience I needed to open my eyes to the extreme food disparity in our country. It made me realize that access to nutrition is not a privilege, but a basic human right.

Nutrition needs to be available to all groups, because only then will this movement be considered a success.