We live in a world full of stigmas and discrimination based off of perceived differences. Mental health is no exception — even the U.S. health system sustains the stigma surrounding mental illness. But this can occur in more subtle ways, too, such as through jokes and everyday lingo.

For example, a lot of people commonly use OCD as an adjective, like, “I’m so OCD.” As a result, it’s easy to forget that obsessive-compulsive disorder is a serious disorder with debilitating symptoms. No, it’s not just having cute little quirks like Zooey Deschanel — still love you, girl.

GIF courtesy of howireacted on tumblr.com

One huge misunderstanding related to this subject is the idea that mental and physical health are separate issues. To put it bluntly, they aren’t disconnected at all. You’d never tell someone with a broken leg or the flu to just get over it and get on with life, right? So, why do we do the same thing to people who struggle with mental illness?

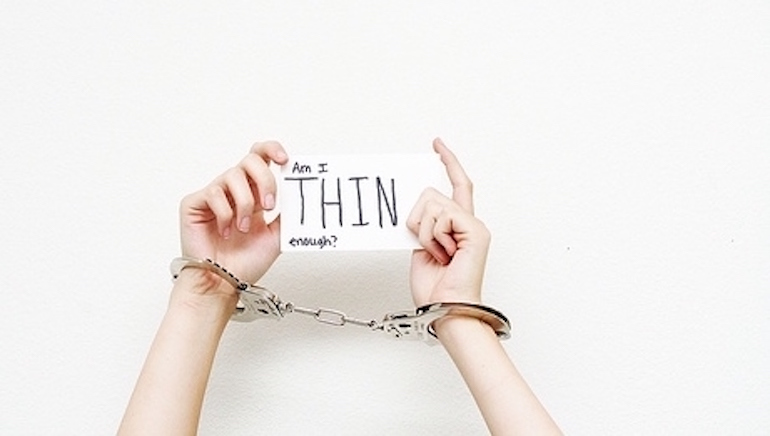

From personal experience, I know that people’s relationships with food and their mental health are interconnected. This explains why eating disorders are so prevalent in our society. However, sometimes eating disorders aren’t so obvious.

In an age where we put healthy eating on a pedestal, it’s easy to get caught up in being so clean and green that we forget to indulge once in a while. And, unfortunately, even treating ourselves occasionally has burdened us with guilt.

When I was a kid, I had the biggest sweet tooth in the world. Not even joking — just ask my parents. I stuffed my face with Fun Dip, Smarties, Starburst, SweeTarts, and the infamous Pixy Stix (the giant blue ones were my personal kryptonite). I ate sugar packets straight up at restaurants. I once pounded four ice cream bars in one night.

Photo by Katie Walsh

Obviously, I had no problem inhaling sugar as a child. But, thanks to my mom’s home cooking, I always ate healthy, balanced meals. My brother and I stayed active, and our plates never failed to pack in a hearty serving of fruits or vegetables. For the record, I never got one cavity.

Weight was never a concern of mine. I loved my sweets, but I also loved being a strong and athletic girl. However, near the end of ninth grade, my body image drastically changed all at once. All thanks to one stupid joke, from one stupid boy.

In March 2010, I was on a spring break trip with my dad, my stepmom, my stepbrothers, and a bunch of their friends. After dinner one night, we were all browsing the dessert menu, and I ordered the brownie sundae. Then, one of my stepbrother’s friends chuckled and said, “Are you sure you need that?”

Despite his muttering, “Just kidding,” I couldn’t enjoy my sundae as his comment replayed in my mind. Even worse, I couldn’t look at myself the same way. I began constantly comparing myself to the other girls on the beach, wishing I could look like them — tall, tan, and skinny. My short, pale, and self-proclaimed awkward body wasn’t cutting it.

Photo courtesy of brothersoft.com

Once I got home, I immediately started working out every morning before school. Even though it meant getting up at 5:30 am, and even if I didn’t feel well, I was on our family’s old exercise bike every day. After my workout, I literally measured out a skimpy bowl of granola with a splash of skim milk for breakfast, calculating every single calorie.

Don’t get me wrong — I still work out before classes, and I love my favorite green smoothie (it tastes like a milkshake anyways, even with a whole cup of spinach thrown in). I don’t see anything wrong with being disciplined about exercise. But there’s a difference between discipline and obsession. And back then, it was definitely an obsession.

That’s where orthorexia comes in. Orthorexia nervosa, though not yet officially considered an eating disorder in the DSM-5, is essentially an obsession with healthy eating. Some people may think this sounds like a ridiculous problem to have in a world facing an obesity epidemic, but it’s more of a struggle than some may assume.

Paired with my obsessive-compulsive tendencies (once again, I’m not talking adorable idiosyncrasies — I’m talking burdensome routines), my orthorexic eating habits consumed me. Physically fit on the outside became a mask for mentally crumbling on the inside.

Photo by Christin Urso

I convinced myself that I was taking care of my body and maintaining healthy habits by being so rigid and restrictive, but I was really just punishing myself for not living up to the idealistic body image that I had formed in my mind. And I soon realized that each pound I lost wasn’t making me feel any better.

Every time I stepped on the scale, which rapidly went from the occasional doctor’s visit to every day to multiple times a day, I felt worse about myself. The pounds steadily dropped, but no amount of weight I could lose would end my mental battle or heal my broken relationship with food.

When I finally recognized that I had a problem, it wasn’t just because of the number on the scale. When I undressed to get into the shower, I noticed the physical effects. I could see the outline of my ribs. My spine protruded from my back. My shoulder blades stuck out. I looked — and felt — weak.

Photo courtesy of genpsych.com

I finally decided to open up and talk with my parents, who were concerned about my physical changes, about my struggle. We agreed that I needed to gain weight in a healthy manner. Putting on weight didn’t mean having late night cereal binges while sitting on the kitchen floor (like I used to do earlier in high school); instead, it meant eating heartier portions of the healthy foods I had been consuming already.

By the following spring, I had gained about 20 pounds and was at my heaviest weight thus far at my height. When I saw the number on the scale, I immediately went back to my problematic mindset. I deeply feared that the number would keep climbing out of my control, and that soon enough, people would be whispering behind my back and calling me fat.

That summer, in Argentina of all places, I lost 15 pounds. Though some of my fellow classmates on the junior Spanish exchange gained that same amount from all of the bread, meats, and sweets the country has to offer, I said no to those culinary delights.

Photo by Hannah Atlas

Out of my fear of gaining weight, I opted for fruit salad for dessert instead of cookies smothered with dulce de leche (thick caramel). I picked at bread for lunch instead of savoring the sizzling steak and chorizo on the grill. I even refused to enjoy flaky medialunas (sweet croissants) that my then-boyfriend bought for me to eat during our last merienda (snack time).

After three weeks abroad, while many of my classmates came home with a bit of extra weight and big smiles on their faces, I returned skinny and voraciously craving broccoli. My parents immediately noticed the change. But I saw the weight loss as returning to my normal — even healthy — weight, so I didn’t bat an eye.

Photo courtesy of Laura Lewis on flickr.com

The next year, I left for college at that same lower weight. Since then, I have steadily gained about 10 pounds. Though I put on most of it this past year (I blame studying abroad in London during the summer, because who can deny the goodness that is afternoon tea?), I must admit that it has been a long time coming.

Over two-and-a-half years later, I feel healthier, stronger, and more beautiful than I ever have. And that doesn’t just have to do with clearing up my acne and building muscle at the gym. It all goes back to mental health. I still wrestle with my body image. I still fight the urge to weigh myself every day. I still panic a little when buttoning my jeans poses a challenge. But, now, I can look in the mirror and choose to love myself.

Photo by Lauren Lahr

So, tonight, I’m going to curl up on the couch with my cat, put on a good movie, eat an oatmeal chocolate chip cookie (with an ice-cold glass of milk — just the way my dad taught me), and celebrate being alive. Because life is short but sweet for certain.