National Food Day was just a couple of weeks ago, on October 24th, a day meant to celebrate healthy, sustainable, ethical food (with a focus on food justice for all). Events and talks were hosted all over the country to promtoe awareness of these issues, a wonderful endeavor that we whole-heartedly support. But just because it’s over, it doesn’t mean we should forget about it all. In fact, I propose that as the new generation of consumers, we start to make everyday ‘Food Day’.

Like fellow Spoon writer Zoe Holland proclaims in her article Millenials May Be “Foodies” But Are They Food Literate?, “it seems as though the greater the interest in cooking, restaurants and health trends, the more truly disconnected millennials are from the system and process in which their food comes from”. The fact of the matter is that food systems in this country are highly controversial. And food education is severely lacking. With food taking on such an important role in our lives, biologically, socially, culturally and economically, it is becoming more and more imperative that each person take a stand and really look at what’s on our plates. Below are some pieces of advice on how we can go about reclaiming the now-derogatory “foodie” title to turn it into a positive, progressive label. (And then we can all go back to making mac n’ cheese with a little more peace of mind and a whole lot more wisdom).

Photo by Lauren Kaplan

To start, get curious and care about where your food comes from. The amount of work that goes into producing a single meal is astounding: from the land it took to grow the food and feed the animals, to the hours of labor and number of hands through which the products were exchanged, to the distance covered in transportation, it really is an effort. For that alone, it deserves to be recognized and appreciated. But more importantly, being educated on food processes is necessary in order to make the best decisions not only for our own good, but also for that of the planet, the global community, and the future.

Look at the food itself. Pay attention to packaging for labels on the provenance of your food, the ingredients (and if you don’t know what something is, look it up to make sure you want it in your body!), and the nutrition facts. Look at the food itself too! If your produce is eerily perfect-looking, it might mean that it wasn’t naturally grown. If it’s covered in dirt, it was probably pulled up from the ground not too long ago. Do some research into your local grocery stores! Ask where they get their food from, or even look it up on the internet in the case of well-known chain stores.

In addition to researching the origins of your food, learn about the various food terms. Words are constantly thrown around in the discourse on food, without actual explanation on their meanings. For example, local and organic foods have come to be equated with sustainable and thus ‘better’ foods, but the concepts don’t mean the same thing and have very different consequences and implications.

Here are some relevant key terms that are helpful to know:

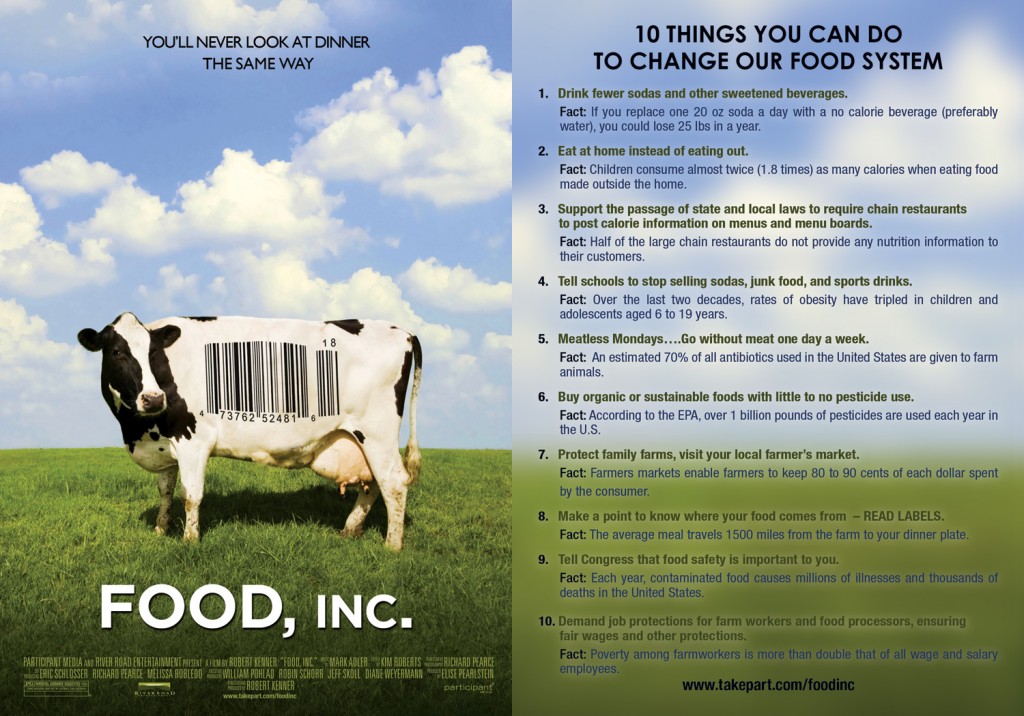

The fact is, there are a ton of dimensions to food issues that pass unnoticed. Natural and organic foods are just the tip of the food movement iceberg, topping a whole slew of controversial topics and an even greater number of people across the planet. In the past few years movies and books with the goal of exposing these issues have been coming out; think, Food Inc., A Place at The Table or the recently released Fed Up, as well as books like Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan or The Globalization of Food, a collection of articles on the nuances of this theme. For more suggestions on movies, read Best Food Documentaries. (Check LT add RP)

Photo by takepart.com/foodinc

Additionally, it’s important to differentiate the symptoms from the causes, and know which ones to act upon. Addressing childhood obesity with campaigns to promote exercise and a healthier mentality about food will certainly help to alleviate the problem, but it isn’t actually getting at the root of why these chronic diseases exist in the first place. Similarly, issues like farmers and workers rights, the lack of nutritional foods in schools, the lack of food access in minority or low socioeconomic-status neighborhoods, the prevalence of cheap junk foods compared to expensive healthy foods, the struggles farmers have in making wage – these are all results of bigger problems. These include but are not limited to corporate monopolies over production (that push out smaller producers and workers), policies regarding food subsidies and more (that impact which foods are cheaper to produce and thus cheaper in the market), zoning issues (that affect potential land usage for agriculture or grocery store development), and decades of initiatives to modernize and industrialize the world, leading to complicated international trade agreements and production chains. Engrained social processes as well as long-standing policies (controlled by a a select few) keep these systems in place.

And don’t forget that all of this is in relation to the constantly growing world population! How to keep it all flowing smoothly and ensure that everyone, inlcuding people in developing nations with little means, have the ability to eat sufficiently and healthfully? These are some of the ethical problems that food activists, producers, and policy makers have to always keep in mind. And much of it is connected. Stay updated on the contemporary issues by checking out your news sources for food-related news. Check out 6 Prime Food News Sites as well as the food sections of your favorite news websites, and even blogs written by food-writers (like Michael Pollan’s) and the TED Talks website for food-related talks. (Link RP article)

At the same time, remember to question the information that is given to you. With so many people involved in food movements and production, and with so many issues at stake, there are obviously going to be disagreements between the different players on what constitutes the truth. For example, if the USDA is funding a study on the health effects of genetically-modified crops versus a privately-owned nutrition association, the results will probably differ depending on what each sponsor wants it to say. The same goes for nutrition labels: the information that goes on it, how it is presented, and what gets left out is influenced by a number of institutions with particular objectives in mind.

The same skepticism should be applied to criticism, too. After learning about the horrors of industrially-produced meats and the impacts of monoculture crops on small farmers, it’s easy to say that the solution to all these problems is to go vegan and only buy from your local farmers. But we also need to keep in mind that there might be other consequences of these decisions; see what this New York Times columnist has to say on why we shouldn’t buy local. So, always weigh different sides of the argument, and come to whatever conclusion most satisfies you.

Photo by Katie Walsh

With all this information in mind, move onto the next step: understanding the implications of your purchasing and consumer decisions. Obviously, with so many uncertainties, it isn’t easy to know for sure what choice is most optimal. Nevertheless, with more knowledge in hand, you’re bound to make more educated choices than without – and at least, you can be confident that you’re doing your best. You can’t unlearn what you discover, and some of the things you do learn are bound to shock you. When you accept the information, you’re also accepting to become a responsible consumer. This is where you pay attention to whom you’re buying from and what your food is; whether you’re supporting a local or a foreign producer; even what the packaging is made from! No one else can do this for you, we all have the power to take responsibility for our roles as consumers before we can demand any kind of change.

Don’t be afraid to voice dissent against something you’re not okay with. Like I said, you’ll most likely be surprised by something you discover, and that surprise might not be good. The one upside is that you can decide to do something about it. Activism can take a number of forms, with some people taking to the streets and others taking to the internet. Get your opinions out there, because if enough people do the same someone has to listen. You can also be active by supporting institutions that you think are worth it. Starting from the top-down by going into food policy and advocacy might be your thing, or maybe you want to go at it from the grassroots level and start farming in a local community garden. If you cook a lot and can afford to do so, try to buy seasonally and support local businesses, or curb your overall food waste by buying only what you need and repurposing leftovers. If you’re really not sure where to start, simply consider retracting your support from whatever institution whose practices you disagree with. By simply refusing to buy products made by ethically suspicious organizations, you can feel confident that you’re creating a break in these otherwise normalized cycles.

Photo courtesy of peta.org

I took a class on the ethics of food production and consumption last semester that prompted me to try out vegetarianism. With the information we learned about how animals are treated in industrial farms and the impacts of an excessively animal protein-based diet on the environment, I felt that I had no other choice but to put my meat-eating on hold until I was sure that it was something I could justify. After a few months I slowly began reincorporating it into my diet in sparse amounts while remaining careful about where the meat was from. I still make a conscious effort to reject that mass produced meat.

Of course, it is crucial to be respectful of others’ individual food contexts. The danger with any kind of increased awareness on a subject is that a sense of arrogance can develop. We might get so into the healthy and ethical food daze that we start to judge other people who don’t behave the same way. While in some cases it is helpful to take on the teaching role and offer advice, it’s important to remember that not everyone has the same flexibility in choosing foods. Some might be limited by money or location (see food security and food access above), and others might be limited for health reasons (serious anemics might not be able to sacrifice red meat, for example). Cultural or religious reasons are just as important too; it might be very difficult for someone who comes from a heavily meat-based food culture to forgo it without forgoing family relationships and values.

My point is, do what you can, but try nonetheless. Question, learn, and put into practice. If everyone put in the effort, imagine how far we could get!

So give a damn! Because it absolutely, no question, affirmitively, is worth it.