Harvard anthropologist Richard Wrangham seems to believe that it does. The former University of Michigan professor returned to the Ann Arbor campus on Friday to explain why.

Photo by Annie Madole

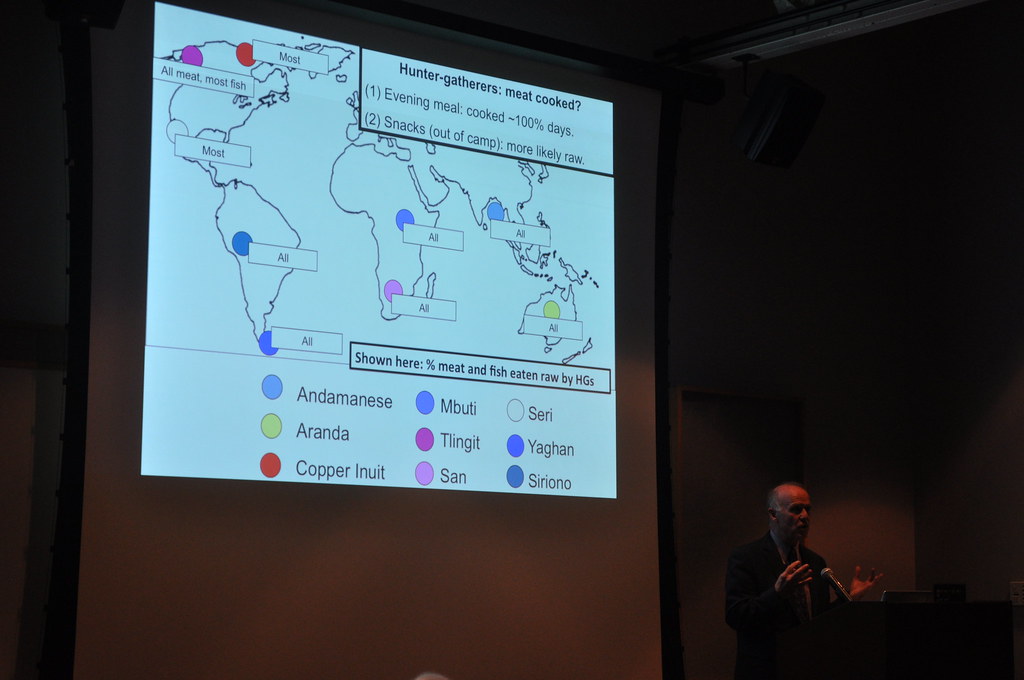

Wrangham argues that as the only species to actually cook their food, at some point in history humans must have adapted to the phenomenon of cooking. The theory is simple: just as all animal species have adjusted to eating specific types of plants or meats, humans have biologically evolved to eat cooked food.

The upside for us? Wrangham’s research proves that eating cooked food, as opposed to the consumption of raw food, increases energy supply. The amount of food processing involved in cooking also lowers the digestive strain on the physical body. This means that by cooking, humans gains more energy per bite as well spend less time digesting their food per day.

Photo by Annie Madole

But so what? Cooked food might be easier to digest, but how does it actually make humans, well, human?

The introduction of cooking, Wrangham believes, marked an evolutionary breakthrough in human development. Cooking itself may be a lot older than we think. Wrangham situates the advent of cooking to about 1.8 million years ago, the time period when humans were evolving from the more ape-like Homo habilis into the freestanding Homo erectus.

Wrangham explained that during this period, sudden species adaptations such as smaller teeth and gut sizes occurred. These changes may have been a direct result of cooking and its changing energy demands being introduced into the human diet. Critics of this theory argue that there is little evidence of early human fire usage by this time period, and therefore little evidence of cooking. However, if correct, Wrangham’s theory could re-imagine human evolution.

First off, cooking would have dramatically affected daily activity time. Instead of chewing and digesting raw foods for an average of six hours a day, Wrangham estimates that cooking would have cut this time down to one hour, creating more time for hunting and participating in other activities. Wrangham is also exploring the effect of cooking on life — focusing on history shifts in human development and on early social interactions. This study examines how protection over food cooked on a hearth might have impacted early gender and mating relationships.

More research into this fascinating look at our history as humans is in the works. As it stands, I’ll need a bit more evidence to be fully convinced. However, Wrangham’s theory is quickly gaining supporters. He may soon change the way we all see our relationship, as a species, to the art of cooking.