Earlier this year, Yale alum and Pulitzer Prize winning writer

1. Where did the misconception of the taste map come from?

photo courtesy of realclear.com

In 1901 German scientist David P. Häing found that taste was not consistent over the entire tongue, although the differences between areas was incredibly small. In 1942, renowned historian of psychology Edwin Boring wrote a book called Sensation and Perception in the History of Experimental Psychology and turned Häing’s study into a graph that made those small differences seem huge. That map you saw in middle school science class was an exaggeration hidden in the 25 pages devoted to taste and smell in the 700 page volume. Over the years people continuously misinterpreted Häing’s data creating a map for the tongue with much more rigid boundaries than actually exist. Sometimes smart people are wrong and we still believe them…oops! Read more about the specifics of this blunder in Chapter 1: The Tongue Map

2. All species started with the ability to sense all five tastes, but some lost them based on their surroundings

photo courtesy of Marc Blackly

Once whales and dolphins migrated from land to sea, they lost the ability to taste sweet, bitter, sour and umami leaving them with only sensitivity to salt. They swallow fish whole, so unlike us they don’t really need to taste their meals! Cats, which ate meat, lost sensitivity to sweetness and the ancestors of pandas stopped tasting umami when they abandoned eating meat for bamboo. Read more about the evolution of our taste sensitivity in Chapter 2: The Birth of Flavor in Five Meals

3. Humans are biologically adapted to eat cooked food

photo courtesy of Mike

Move over paleo diet, animals (including us humans) use much less energy when digesting cooked food than raw food. The advent of cooking most likely helped with brain growth in Homo erectus 2 million years ago. Keep reading Chapter 2 to tell off your aunt who wants you to go paleo.

4. Taste is like a snowflake

photo courtesy of Alexey Kljatov

Our palates are effected by our environments, life experiences and the differences in our DNA. No one tastes in the exact same way as anyone else: even within families tastes can vary widely. A compound used in formulas for blue dye, PTC, was accidentally ingested in a factory. Some people found it tasteless while others found it unbearably bitter. This discovery affirmed that tastes are wildly different. Scientists have even been able to isolate a specific gene for bitter receptors. Read more in Chapter 3: The Bitter Gene to explain to your parents why you still won’t eat your vegetables.

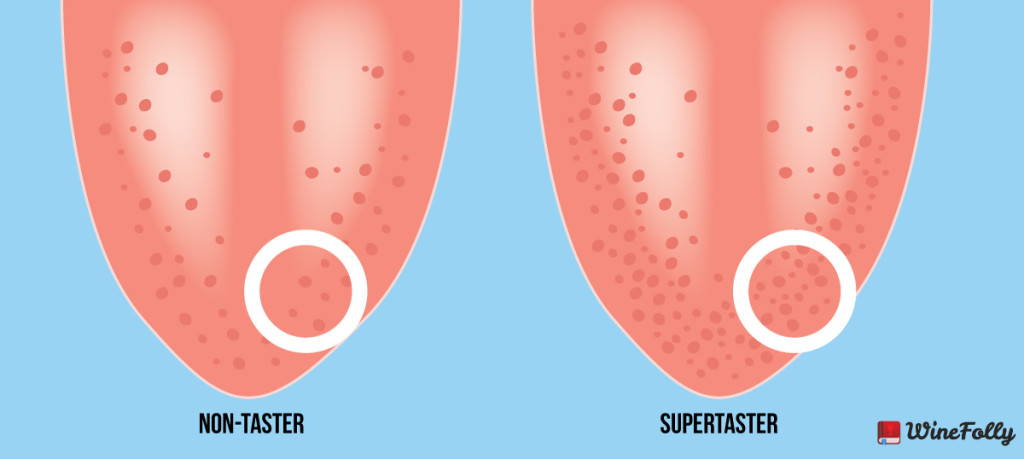

5. The concept of supertasting was discovered at Yale

photo courtesy of winefolly.com

Linda Bartoshuk, a taste scientists here in the 70s, found that some people have many more taste buds on their tongues than others and have a heightened sense of taste. This discovery meant that taste genes had the ability to influence the anatomy of the tongue and nervous system. Keep reading Chapter 3 to find out what supertasting is linked to and test yourself to find out if you’re a supertaster.

6. Proust’s madeleine makes sense

photo courtesy of Karen Booth

Flavors can bring up a piece of a childhood memory and your brain can connect that piece to recall the rest of the memory. Memories can also make foods taste differently, so don’t think of that time you got food poisoning eating sushi next time you go for all you can eat at Sushi Mizu. Read more about these connections in Chapter 4: Flavor Cultures.

7. Umami alone has no taste

photo courtesy of Joan Nova

We’ve all heard of umami, the savory taste, but did you know that there is no definite taste of umami? If you take a sip of pure, dissolved glutamates you won’t really taste anything. Umami’s power comes from its interaction with other flavors, enhancing them to create some of our favorite foods. Keep reading Chapter 4 to learn about these interactions.

8. Miracle berries are used to help cancer patients

photo courtesy of Rachel Patterson

Chemotherapy can kill taste bud cells because they grow quickly, like cancer cells. The drugs also travel in the blood stream, causing patients to think everything tastes bitter. In come miracle berries; the protein miraculin in them blocks sweet receptors, depriving sugar of its sweetness, but also turns acidic foods sweet. The more sour the food, the sweeter it tastes. Read Chapter 5: The Seduction to learn what sour foods taste like after you’ve swallowed some miracle berries.

9. Sugar plantations inspired the first wave of vegetarianism

photo courtesy of John Payne

In 1660 Thomas Tyron left London for Barbados and was shocked by the harsh reality of sugar plantations. They were nothing like the harmonious fields he had imagined. He returned to England and 20 years later he wrote on his philosophy of taste, speaking out against indulging the appetite. His views inspired a vegetarian movement, including Ben Franklin! Another fun fact from Chapter 5–the word dessert comes from the French desservir which means “un-serve” like clearing the table at the end of the meal.

10. An early sweetener was actually poison

photo by Jocelyn Hsu

The Romans boiled crushed grapes in pots made of lead to make sapa syrup that they used to sweeten both wine and foods. The active ingredient in this syrup, lead acetate or “sugar of lead,” is toxic. Could Rome have fallen from lead poisoning? Did Pope Clement II and Beethoven, who both mysteriously dropped dead, also die from their love of lead sweetened wine? The world may never know, but Chapter 5 can tell you about the safer sweeteners we use now.

11. A chemist started the myth that searing meat seals in juices

photo by Kathleen Lee

Justus von Leibing was a chemist who turned his focus to food. He popularized the theory that most of the essential nutrients in meat lie in the juices and that searing is the only way to keep them from burning off. This theory went against historical practices, but it proliferated and soon cooks were serving dry meat and insisting it was full of juices. Read the end of Chapter 6: Gusto and Disgust to learn about how browning meat can actually be beneficial to taste.

12. Heat is not actually a taste

photo by Sarah Strong

Although eating something super spicy can make you uncomfortable, chili heat doesn’t cause you lasting pain. Your digestive track might not be happy, but spicy food is pretty much harmless. Birds can’t even taste capsaicin, the stuff that makes chilis spicy. Chili heat is not a taste because it causes a burn on the outside of your lips where you don’t have any taste receptors. We all know the burn from spicy food is a very real pain, but it does go away. Learn about the quest to grow the hottest peppers in the world in Chapter 7: Quest for Fire

13. The lab grown burger did not taste good

photo courtesy of euronews.com

In 2013 Dutch scientists cultured meat from adult cattle stem cells and grew enough meat to create some burgers. The meat lacked fat and influence from the cow’s diet and environment. The burgers weren’t even red–they had to be dyed with saffron and beet juice. Apparently these lab grown burgers didn’t taste like much–especially not like meat. One day, with the addition of fat, these burgers might be palatable, but it’s unlikely that they will taste anything like the real thing. Read more about food substitutes, including Soylent, in Chapter 8: The Great Bombardment

I leave you with two more fun facts: you know when you eat too much salt and it’s just gross? That’s because it tastes like a mix of bitter and sour, yuck! To get rid of that horrible flavor, crack a grain of pepper in your mouth then drink some coffee–it will taste as sweet as if you had stirred in a tablespoon of sugar!