Spoon Northwestern teamed up with Food & Wine magazine to increase awareness about the problem of food waste on our campus. The following project was completed with a grant of $500.

News alerts buzz on my phone throughout the day. One minute I read about recent acts of terrorism or environmental disasters, and the next minute, I’m alerted to Donald Trump’s verbal debacle of the day.

Amidst the chaos of the daily news, though, the issue of food waste is foreboding and often overlooked. A group of Northwestern students and I concocted a plan to get students’ attention for this increasing problem.

The issue

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Bloom on flickr.com

The food waste situation has joined the ranks of top issues facing our globe. According to the National Resources Defense Council, 40 percent of food in the United States goes to waste each year, although studies have shown that much of this food is still safe to eat. Economically speaking, this amounts to approximately $165 billion worth of food wasted each year.

There are two very key ways in which food waste affects the planet. First of all, wasted food ends up in landfills where it breaks down and produces methane, a greenhouse gas that is a more potent contributor to global warming than carbon dioxide.

Photo courtesy of foodbeast.com

The second reason is simple: people are starving. How can we rationalize wasting food in the U.S. while 1 in 6 Americans don’t know where their next meal will come from? Considering hunger in the United States, the statistics are hard to swallow.

Why do we waste?

Photo by Natsuko Mazany

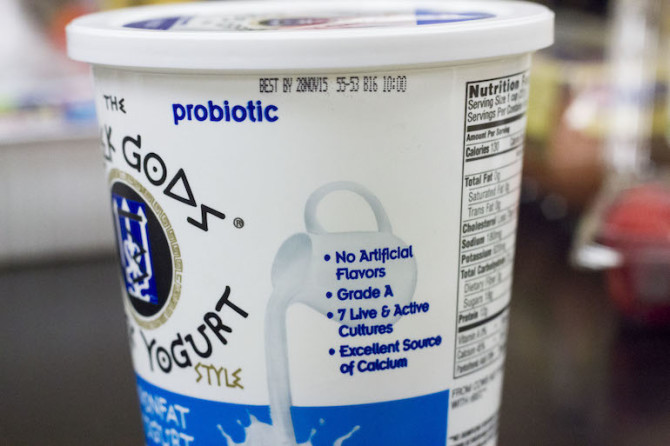

In wealthy countries, most food is wasted and lost at “later stages in the supply chain” – for example, customers leaving food behind at restaurants. However, in developing countries, food waste and loss occurs mainly in the early stages of production and distribution, because of a lack of transport and storage infrastructure, as well as technical limitations. Additionally, expiration labels are much to blame. Labels with “sell by” and “best by” dates are placed on products to indicate when they decrease in quality.

However, many manufacturers use this as a way to maintain a quick turnover rate in grocery stores, benefitting from the common misconception among consumers that the dates reflect when food is unsafe. As a consumer, this perpetuates the uneconomical cycle of buying food, throwing it out on the expiration date, and then returning to the grocery store to buy more. Without the knowledge to differentiate between expiration labels and the know-how to determine when a product is actually rotten, consumers will unknowingly continue to follow this cycle.

Why tackle the issue on college campuses?

Photo courtesy of Nazareth College on flickr.com

Approaching this problem on a college campus is especially relevant. Dining halls, home to hoards of undergraduates and all-you-can-eat buffets, amass huge amounts of food waste. According to Recycling Works, the average college student generates 142 pounds of food waste each year. Here lies an extraordinary opportunity for colleges and universities to catalyze change in students and future generations simply through the sustainable practices they adopt.

While there are effective long-term solutions to the food waste problem, like providing compost kits for students and initiating food-recycling programs in dining halls (see Campus Kitchens), we need to start with incremental stepping stones.

Our first step?

Photo by Ally Mark

Going into the project, we decided our aim was to educate college students about reducing their food waste, through a better understanding of food shelf life and expiration labels. This knowledge could induce easy, but significant changes in how students purchase, eat, and dispose of food.

On Wednesday, Dec. 9th, Spoon Northwestern and Real Food at Northwestern hosted a one-day experiential event.

Photo by Ally Mark

Stationed at a central location on campus, we offered free samples of three different Spoon recipes— but there was a twist. For the sake of high shock-value, a portion of the ingredients had expired. The truth is, these ingredients were still safe to eat according to an established “food shelf life index” that draws data from governmental agencies such as the FDA and USDA. Also, just as important, we evaluated the food with our own judgment and common sense.

Photo by Ally Mark

We waited as groups of students approached our table. After each person took a sample, we asked to film their reactions as we were “testing out new Spoon recipes.” What did students have to say about the food? We heard everything from “delicious” to “so fresh” (yes, this is in reference to expired blueberries).

Photo by Ally Mark

Imagine their faces when we then asked, “What would you say if we told you that some of these ingredients are expired?” Surprisingly, most students didn’t even mind. In fact, no one was anywhere near as appalled as we’d predicted. A majority of them even declared they were fine with it, simply because the food tasted and looked fine.

Photo by Ally Mark

Truthfully, the positive feedback may have partly been due to the fact that college students are rarely bothered by what others might find ‘gross.’ The truth is, however, an amazing amount of students were already knowledgeable about eating expired food.

Watch their reactions below.

The light at the end of the tunnel

Photo by Ally Mark

As annoyed or surprised as students were, their reception to the idea of expired food was great once we reassured them that the food was still safe to eat. On top of that, a majority of students stated that this knowledge would influence how they purchase, use and conserve food in the future.

To solidify their newly garnered knowledge (and, perhaps, as a thank you token for putting up with our scheme), we also handed out original magnets with shelf-life infographics of foods we think are tricky or ambiguous to tell when they’ve gone bad – check it out:

Photo by Ally Mark

After an afternoon of educating students about food waste, expiration labels, and breaking down the stigma that exists around food past its prime, we heard the dialogue changing. People understood food might be past its prime, not past its safety limit. The next day, at a dinner with friends, I smiled as I saw every plate clean at the end of the meal.

Moving forward

If you’re now thinking, “hey, how can I help the food waste situation in the world?” (hopefully you are), these are for you:

This change in perspective needs to be facilitated by more than simply the Northwestern students who experienced the event firsthand. Hopefully, it is a universal lesson in teaching people simple and easy ways to cut down on food waste, regardless of age, demographic or lifestyle.

Again, a project like this is just the beginning. I encourage all you college students (or anyone reading this article) to first make a change in your own eating habits. Then, try to plan your own event or mini-project: host an ugly produce dinner party, print a shelf-life infographic for your roommates or initiate a compost system in your school’s dining halls (while you’re at it, you could share this article!). Be the catalyst in your community and reduce food waste.

Special thanks to Food & Wine Magazine for the funding of this project, and to Northwestern students Miranda Cawley, Audrey DeBruine, and Emma McVicar (videographer) for their collaboration.