Lions are often described as strong, powerful and courageous. Nicknamed the “Kings of the Jungle,” these fierce beasts bring images of the sprawling African Serengeti to our minds.

Photo Courtesy of ispilledmyink

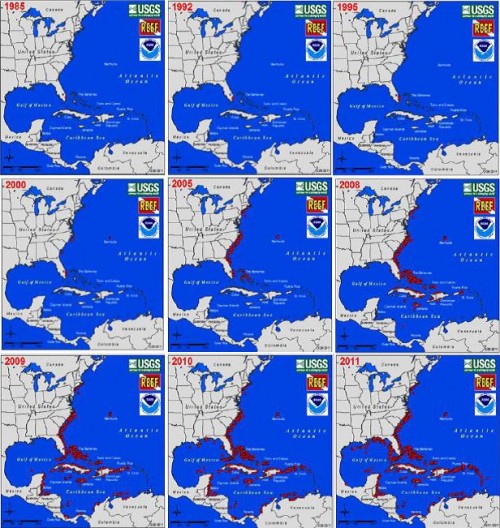

What many people don’t realize is that they’re contributing to the destruction of the Atlantic Ocean’s ecosystems, in the form of marine animals. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the spread of lionfish along the U.S. eastern seaboard, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean is the first documented case of a non-native marine fish establishing a self-sustaining population in the region.

Lionfish call the Indian Ocean, western and central Pacific and the waters around Indonesia home, living on reefs and in lagoons. Fully-grown lionfish can range from between 2 and 17.7 inches, weigh up to 3 pounds and live for as long as fifteen years. Lionfish sport red, cream, white and black stripes. They’re incredibly skilled hunters, eating small fish, invertebrates, mollusks and each other. Thanks to their poisonous spines, lionfish have few natural predators.

Photo Courtesy of Shayne Heffernan

Many are wondering how lionfish managed to make their way to the Atlantic. It can only be traced back to a freak accident. In 1982, a South Florida aquarium was damaged by Hurricane Andrew. Six lionfish apparently escaped from the ruined facility. The rest is history.

Cold water in northern parts of the Atlantic keep their numbers in check. Unfortunately in the south, lionfish are quickly spreading through the South Florida Estuaries, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

Photo Courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey

Lionfish reproduce at a young age and do it quickly, releasing up to 2 million eggs per year. They’re not picky eaters and have been shown to feed on more than 50 different species. Lionfish aren’t ones to watch their figure either. After a meal, their stomachs can expand up to 30 times their normal size.

Photo Courtesy of Erin Cziraki

These habits are hitting the seafood industry hard. Lionfish are rapidly consuming snapper, sea bass and lobster, all of which are economically important. They are also dominating native population’s food supplies and habitats, leading to disorder in the food web and ecological system. “Lionfish are voracious predators and are taking the already threatened Caribbean reefs by storm”, says scientist Jess Wurzbacher.

In the past few decades, marine scientists have been taking this issue seriously and trying to find solutions. In 2012, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Centers for Coastal Ocean Science wrote Invasive Lionfish: A Guide to Control and Management. Lionfishing derbies have proven to be successful too. Competitions in Florida and the Caribbean have led to the capture of thousands. Since 2010, conservationists at Honduras’s Roatan Marine Park have been training sharks to eat lion fish, in an effort to lower their numbers.

Photo Courtesy of Antonio Busiello

Fishermen in Jamaica have lost a great deal to the lionfish. They’ve adapted by incorporating lionfish into the cuisine, and now use the invasive species to generate a profit.

Everyone can contribute to the cause by adding lionfish meat to his or her diet. In June of 2011, the NOAA launched the “Eat Lionfish” Campaign, encouraging people to take part in the effort to lower the population. High in Omega 3 fatty acids and low in saturated fats and mercury, lionfish are a healthy choice. A number of restaurants in the Caribbean, Latin America and the United States have added lionfish to their menus.

Photo Courtesy of Akumal Living

Preparing lionfish yourself is easy too. Try it in fish tacos with pico de gallo, black beans, sour cream, lettuce and cheese. Or cook the meat tempura style using ginger, garlic and rice vinegar. There are a number of delicious and creative ways to serve lionfish. If you’re feeling adventurous, fry the fish whole like they do at La Latina Grill, a restaurant in Curaçao.

Photo Courtesy of La Latina Grill

This issue demands our attention. If the population continues to rise at this rate, the seafood industry and marine environments will change drastically. So do your part by chowing down on the tasty, flaky meat of the lionfish. Our oceans will thank you.