Indiana University students at Oxfam’s global food inequality simulation gathered around in anticipation of a shiny ticket. Students drew tickets at random and were assigned an economic status (upper, middle, or lower class) based on their draw. These statuses corresponded to how each participant would be able to interact with the food provided. This event gave students the opportunity to learn about global food disparity through a simulated experience of poverty.

The three different colored tickets represented three different income levels: the 20% of people in the world who earn at least $6,000 a year (the upper class), the 30% who are making between $1,032 and $6,000 (the middle class), and those on the poverty line who make less than $1,032 a year. Fifty percent of the world falls within the poverty-stricken category.

Photo by Sabrina Dorow

According to their website, OxFam is “one of 17 members of the international Oxfam confederation” and “work(s) with people in more than 90 countries to create lasting solutions.” Their mission is to “create lasting solutions to hunger, poverty, and social injustice.” It makes sense then, that they would host such an eye-opening event about the chance that we are born into a wealthy, industrialized nation.

I was one of the audience members to draw a silver card, which symbolized the lowest income group. While those who had drawn the middle and upper level cards made their way to their tables, I felt a sense of hopelessness. We sat on a black blanket on the floor, while the rest of the audience sat propped up in comfy couches and chairs.

Photo by Sabrina Dorow

The MC told stories about members in each of the groups and some people moved between class systems – losing land and gaining job opportunities were two of many causes of class shifting. The focus switched onto those of us who had drawn silver cards, and the MC began to tell the story of the members of our group (based upon real experiences by real people around the world).

“The majority of the world makes less than 1,032 dollars every day,” he tells the audience, “every day is a struggle to meet your family’s basic needs. Women walk 5 to 10 miles to get water, take care of the children, and often eat less so everyone else has enough. You don’t get the minimum number of calories you need, and while you’re working, you must give your landowner 75% of your harvest.”

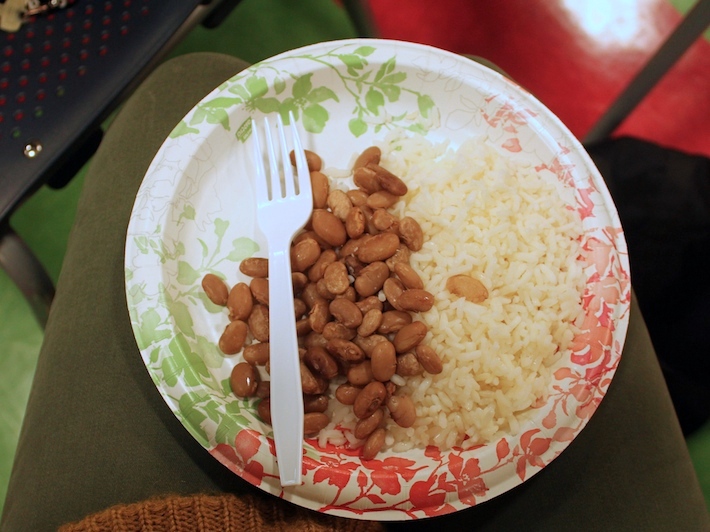

By this point, the smell of food from the table was wafting through the air, making my stomach grumble. There was rice for the lowest income group, rice and beans for the middle income group, and Mother Bears pizza and cookies for the highest income level group. The upper-class group also sat at a table.

Photo by Sabrina Dorow

Photo by Sabrina Dorow

Then the MC had a woman from the lower income group and a man from the highest income group both stand up.

“The high income man is likely to outlive her by 15 years,” the MC reads poignantly.

These facts are real, they are overwhelming, and they may seem daunting. So what can we do? After receiving our meals and heading back to where each of the other members of our group was sitting, IU students discussed their opinions on what changes could be implemented within the campus.

“For things like this to change would mean people have to make a conscious effort to purchase things from companies that engage in fair trade,” said Kate Shirk. She gave the example of shopping at Walmart and the Dollar Store, and explained how she sometimes felt unsure of the integrity behind such cheap prices.

According to fairtradebloomington.org, there are currently 27 food and retail stores in Bloomington that support fair trade. To be on the list, a store needs to carry at least two fair trade items.

“The vision for Fair Trade is to create opportunities for economically disadvantaged artisans and producers, set a fair price by artisans and producers, promote gender equity, ensure safe and healthy working conditions, promote responsible environmental practices, and an opportunity to build long-term relationships with artisans and producers that create economic opportunity.” –Bloomington Fair Trade

The part of the mission that stands out to me most is the goal of ensuring safe and healthy working conditions. If we want to create change in the world, doesn’t it make sense that safety comes as a top priority? If we want to create long-lasting sustainable food economy, doesn’t it make sense to bring opportunities and place value on the people working and living in these poverty-stricken areas?

Aamina Khan was in favor of bringing the culture of sustainability to IU’s campus.

“We have the biggest farm produce in Indiana, there’s so much to do locally that embodies the attitude (of sustainability)”, she says. She also brought up something I hadn’t ever thought about: eating less meat in an effort to conserve more water. As she learned in a documentary, the cost of feeding animals is extremely high; it’s much more sustainable to feed more people with plants.

Kate Shirk proposed the idea of a “meatless Monday” on campus to promote more sustainable eating, but Aamina added that “going vegan for lunch would not be as much of a drastic change” for the community.

“The one thing I’d like everyone to remember,” the MC read, “is that everyone has the same basic needs; the culture we are born into is the only difference. As each one of us walked in the door today we can look around and see that equality and balance doesn’t exist here.”

So even though I got to go back to my house and make a more substantial dinner (along with an abundance of pizza that the higher income group graciously let us take home with us), it was an eye-opening experience to feel the simulated inequality (if only for an hour) of the food systems across the globe, and the privilege of being born into an upper class home (remember that an upper class home is defined as one that makes more than $6,000 a year, which is definitely not what is considered upper class within the US economy). No matter where you’re reading this, ask yourself how you can get involved in your community, school or within your own home: sustainability is a conversation that requires thoughtful minds and resourceful action.